mathematical imperfection

The next time you hear an instructor talk about 'perfect rhythm' or 'perfect time', please tell them that these things are impossible. I will show you why.

Let's look at the standard 8 on-a-hand exercise at an easy tempo of 120 beats per minute. We do some math and find that the amount of time between each note should be exactly 0.25 seconds. When I say 'exactly', I mean 0.25000000000000000000000000000000. seconds.

The best snare drummer in the world plays the first note of the exercise and we start our better-than-atomic clock. He is already screwed when he attempts to play the second note of the exercise. We have defined a single point in time when that second note should be played. Since a point in time has infinitely small length, the probability of playing a note at that point in time is EXACTLY ZERO. There is not a very small chance that he plays the note at the perfect time, even if he tries really hard and practices a lot. Mathematically perfect rhythm is impossible!

Ignorance is Bliss

Thankfully the human ear is not perfect. Can you imagine going to a drum corps show where every single note sounds dirty? It would not be enjoyable at all. Personally, after my first few drum corps shows as an audience member I was so blown away that I could barely sleep the following night. I was simply amazed at the level of performance and execution. Now, I usually leave drum corps shows feeling slightly disappointed that only one drumline almost played a clean show. Ignorance is Bliss.

Humanly Perfect Rhythm

What do I mean by 'humanly perfect' rhythm? I am talking about rhythm that is 'close enough' so that the human ear cannot distinguish it from mathematically perfect rhythm. So, how close is close enough? It turns out that our ears have a minimum amount of time from which we can distinguish two different impulses of sound. This is called time resolution. The resolution for the human ear is around 0.02 seconds. This means that if we hear a sound being produced less than 50 times per second, we will be able to hear each individual pulse. Anything faster than 50 times per seconds will sound like a steady tone.

A good example of this in snare drumming is the buzz roll. When a buzz roll is played correctly we hear a continuous buzzing sound. This is because the individual vibrations of the stick against the drum head are occurring faster than 50 times per second. If we play an open stroke roll as fast as we can, we can still hear every individual note. For reference, 50 notes per second is equivalent to a 32nd note roll at 375 beats per minute (good luck!!!)*

*Depending on the tuning of the drum, the duration of each note will cause the individual notes to blend into a continuous sound well before the 50 notes/sec threshold is reached.

Varying levels of 'clean'

Have you heard the terms 'high school clean', 'college clean', or 'piss clean'. All of these terms describe different levels of cleanliness with which a line can play. I will describe my definition of each of these levels below:

High school clean: Many lines never reach the level of humanly perfect rhythm that I described above. They will commit rhythmic errors so severe that one can actually distinguish the individual notes from player to player. My personal definition of high school clean is when ~90% of the notes played don't contain these blatant rhythmic errors.

College clean: Once a line can play 95-100% of their notes without blatant errors, I would consider this to be college clean. While nearly all of the notes are lining up mathematically, there is still a 'thick' quality of sound that the line is producing. This thickness arises from a few sources:

1) Minor rhythmic errors are present across the line that will tend to 'thicken' the duration of the combined notes from all players.

2) The sound each player is producing is slightly different because of the following:

a. Variation in stick weight / pitch

b. Variation in stick velocity (volume)

c. Variation in note placement on the drum head

d. Variation in tuning of the drum head

Piss clean: Every so often a snare line comes along that reaches the status of 'piss clean'. At this point a listener can not distinguish the sound of the entire snare line from the sound of a single snare drum. To achieve this state of snare drumming bliss, a line must eliminate all of the variations mentioned in the above section. This is no easy task, especially given the musical and movement demands in modern drum and bugle corps! My personal favorite example of a piss clean line is the SCV 1992 snare line. I have a VHS recording of a show warm up that is absolutely phenomenal!

The importance of tuning

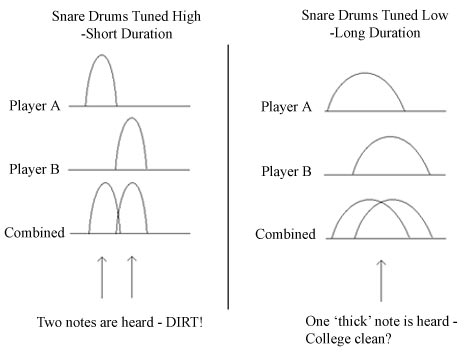

Depending on the skill level of the snareline members, it is often not a bad idea to 'tune out' a lot of the rhythmic errors. This simply means tuning the snare drums such that the duration of each note is long enough to mask the variations in rhythm from one player to the next. The shorter the duration of the note, the more apparent the rhythmic errors will be. I demonstrate this graphically below:

Conclusion

While in many cases ignorance is bliss, developing your ear to hear very minor rhythmic and sound quality errors will allow you to fix these errors and achieve levels closer to mathematical perfection. Also, understanding the challenge and improbability of achieving 'piss clean' will give you a huge appreciation for lines that reach this status. When you witness these lines, you will know that you have just seen something special.